First: what does it mean when someone in politics is accused of sounding a 'dog whistle'? And why does the canine metaphor continue in the term 'red meat'?

Then: aces are wild as we explore some of the words and phrases from the card table.

Download the episode here.

Transcript

Emily Brewster: Coming up on Word Matters: dog whistles and red meat. And then we'll deal you in on some phrases from card games. I'm Emily Brewster and Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media. On each episode, Merriam-Webster editors Neil Serven, Ammon Shea, Peter Sokolowski, and I explore some aspect of the English language from the dictionary's vantage point. The parlance of political commentary moves fast and often paints a vivid picture as it goes. That's where we're starting today with Ammon Shea diving into two fairly new and very evocative terms, dog whistle and red meat. Listen carefully.

Ammon Shea: If you spend any time following politics, or following somebody who follows politics, you probably in the last few years have come across the expression dog whistle, referring to something other than an auditory signal it means to a dog. It is something that we defined within the context of politics as an expression or statement that has a secondary meaning intended to be understood only by a particular group of people that is often used before another. Now, this is an interesting shift in the meaning of dog whistle, and dog whistle of course has a fairly obvious thing, which is that it's a whistle to call or direct a dog, but especially it's one that sounds at a frequency that is inaudible to the human ear. And so dog whistle, say politics, dog whistle legislation, dog whistle speech is very, very similar in a way. It's just a kind of shift, a figurative shift to the left or the right. It's a fairly recent shift. The original dog whistle, I don't know how old the actual implement is. Our earliest written evidence of them comes from about the end of the 18th century. It comes up in John O'Keeffe's work The Irish Mimic, which was published in 1795 and character in this play has the line "as to battering pewter pots against men's foreheads and making cravats of their kitchen pokers, that's all to me a mere dog's whistle." So dog's whistle rather than dog whistle, but obviously fulfilling the same lexical function there. Now, in terms of when it took on the political meaning, it's actually very, very recent. And the earliest evidence that we've seen comes from the Oxford English Dictionary, who found it in a Canadian newspaper, The Ottawa Citizen, and they have it from 1995 as the earliest figured abuse. I've looked into this myself. I have not yet seen anything before this. Could have come up before, but it's not in widespread use certainly.

It does come up, not in figurative use per se, but as a similarly, there was a book in 1947 titled American Economic History. And in the book they refer to a speech, President Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as being quote, "designed to be like a modern dog whistle with a note so high that the sensitive farm ear would catch it perfectly, while the unsympathetic ear would hear nothing."

Peter Sokolowski: That's it.

Emily Brewster: That's it.

Ammon Shea: It's close.

Neil Serven: It defines it for us.

Ammon Shea: Except that it's a simile rather than a figurative use. So we don't count that as actual evidence. So...

Emily Brewster: It's not an instance of the term in use, but it lays the groundwork for the term.

Ammon Shea: Exactly. It shows that people were thinking about dog whistles in this way in 1940.

Peter Sokolowski: And explaining it very clearly.

Ammon Shea: Very helpfully for us. But the actual use of it is really quite new. And in a way, it reminds me of another term which comes up often in a political sense, which is red meat, because we often hear about politicians throwing red meat to their base. And in a political sense, red meat is the little older than dog whistle. It goes back to the 1940s. And before that it was used as a way of advertising motion pictures. Red meat as a term is actually about as old as dog whistle, they both come up from the 1790s. I mean, our earliest citation for red meat is in a George Coleman play. And it's interesting that both of these come up in plays because I think that a lot of times theater serves as a useful corpus of use because it more often replicates spoken language.

Peter Sokolowski: Yeah.

Ammon Shea: And so in a way you actually find terms, particularly idiomatic terms, that come up earlier in this sort of replication of spoken language.

Emily Brewster: Right. A kind of orchestrated spoken language.

Ammon Shea: An orchestrated colloquialism, exactly. So this is a George Coleman play called The Surrender of Calais. And a character says "here's meat, neighbors, tears from your eyes and make your mouth water." However, the sense of red meat, like something substantial that can satisfy a basic need or appetite. So there's a citation from an industry paper titled The Nickelodeon from 1911, "An exchange manager recently complained to me of the lack of sensational subjects. His actual words were they, the public, want red meat and they want it raw." The following year, a citation from the Moving Picture News in 1912, "He told how ministers, representative citizens had condemned the motion picture shows. And when he investigated it, the real red meat of the situation, the principal objection, seemed to be because of the price of admission was cheap." And then in the 1920s, we start to see the term in advertising copy for film. So an advertisement from 1928 from the movie Greased Lightning described it as "The red meat sort of picture you will remember for weeks."

Peter Sokolowski: It's being used in popular print media so that it's presumed that people understand it.

Ammon Shea: Right. In 1926, an ad for a movie called The Rainmaker called it quote, "A strong red meat love drama." So it's a very clear figure of use. And then again, in the 1940s, we start to see red meat turn into a political term.

Emily Brewster: It's a little unsettling, how both dog whistle and red meat in the realm of politics are really saying something about the animal nature of the voter.

Neil Serven: Yeah. They seem to both have this idea of getting the voters to come to you, right? If you throw in red meat, you're kind of throwing them into the animal pit or whatever, and the tigers go running after it, or blow the dog whistle and this certain subset of people that will understand what you are saying will then pay attention to you. That's essentially what it's about.

Emily Brewster: It's definitely about manipulation by the one who is wielding the tool or the nourishment.

Ammon Shea: It doesn't convey a feeling of appealing to one's higher nature.

Peter Sokolowski: The political use of colors, red meat, and also the term red, which originally meant communist or of a relating to a communist country and especially to the former Soviet Union. But paradoxically also in American politics more recently means tending to support Republican candidates or policies. It's sort of odd that of all the parties, Republicans are called the red states. And that was sort of arbitrary because I think on election night, the maps would show different colors.

Neil Serven: I believe they switched at one point because there used to be old elections where blue would refer to the Republican and red would refer to the Democrat. And then I think they weren't really fixed to one party or the other from year to year or election to election. And then eventually settled around the one color, then red for Republican and blue for Democrat.

Peter Sokolowski: It's only since the election of 2000 that we refer to red and blue states in this way. Whereas before that, they were just discriminating them arbitrarily just to show one side or another, and they could have used any two colors.

Neil Serven: Presumably they use the patriotic colors and that's what they just flipped them back and forth.

Peter Sokolowski: Exactly.

Neil Serven: But there's a lot of other interesting political language that has survived even from the 19th century. We refer to muckrakers and carpet baggers. And I believe earmark once referred to how cattle would be sorted out. You talk about your earmarking spending, you would mark the cattle by their ear.

Peter Sokolowski: And pork barrel.

Neil Serven: And pork barrel. And it's interesting that this kind of these terms that make you think of agriculture and maybe farming and a lot of them have kind of stuck around for these political applications.

Ammon Shea: We most often now hear about maverick in large part because of John McCain and the association with that name. And that obviously came from cattle.

Emily Brewster: We should tell the whole story because not all the listeners know the whole story.

Ammon Shea: Will you tell the whole story?

Emily Brewster: There was a rancher whose name was Maverick, and he refused to build fences. And so his cattle would roam, much to the chagrin of his neighbors, and people would just steal his cattle because they would wind up on his property. And so he branded his cattle with his name. He was a "maverick" in doing this.

Ammon Shea: Uh huh.

Emily Brewster: You are listening to Word Matters. I'm Emily Brewster. After the break, we'll deal you a new hand of words. Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.

Neil Serven: I'm Neil Serven. Do you have a question about the origin, history or meaning of a word? Email us at [email protected]

Peter Sokolowski: I'm Peter Sokolowski. Join me every day for the word of the day. A brief look at the history and definition of one word available at merriam-webster.com or wherever you get your podcasts. And for more podcasts from New England Public Media, visit the NEPM podcast hub at nepm.org.

Emily Brewster: Long before an evening's entertainment involved Netflix and chill, a night of pleasant diversion among friends often involved a deck of cards. The sound of shuffling cards may have faded from cultural prominence, but our language is riddled with idioms that echo it. Here's Neil Serven going all in on words from the card table.

Neil Serven: We have a phrase in English that we use for something that presents an unknown or unpredictable factor, and that is wild card. Here's an example in Cosmopolitan: "Informing my mother was tougher because she and I are not close. She's always been a wild card emotionally overreacting to minor things." It's pretty clear what that means. It's like, you don't know what you're going to get from this person. So an example from the AV Club about, I believe it's the show Game of Thrones, "Everyone's eyes are in the sky in the clip as Rhaegal and Drogon soar over the huddled masses inspiring everything from awe to fear to whatever the hell Cersei's doing. She's the wild card in all of this we venture. Will she join the new queen, aid her enemies and eradicated the knights king's army, or will she simply sip her wine as the world burns?"

So wild card obviously comes from card games. A wild card is a card like a deuce or a joker, it can be used to stand in for any card as designated by the holder. There was no real pre-existing use of wild before that, strictly as an adjective, before it became used in the term wild card. But then we later would use it in phrases like "the joker is wild" or constructions like "the deuce is wild." It's not really hard to see where this came from. Something like an animal that is wild is likely to stray. You don't know what it's going to be. So you don't know ahead of time what the card is a deuce or a joker is going to be until you need it.

Emily Brewster: I think it's interesting that the wild card in a card game is a card you want, right? Oh, I've got this card. I can play it in any situation because it can be any kind of card. But if you're looking for emotional support from somebody who is emotionally a wild card, you're not going to get what you want.

Neil Serven: You don't know if they're going to help your hand the way a deuce or a joker might, right?

Emily Brewster: That's right. So you want to have the wild card. You don't want somebody to be a wild card necessarily.

Neil Serven: Right.

Emily Brewster: Or if you are, you got to keep your fingers crossed because maybe they'll behave in a way that you don't want them to, or maybe they'll behave in a way you do want them to.

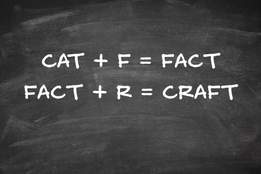

Ammon Shea: It's also interesting that wild card is then taking on further extended uses, which is in terms of computing. It could be a wild card character, which could be again, anything that you want it to be. So as somebody pointed out, it's not necessarily desirable in a partner, but it is desirable in a poker game or in boolean logic.

Neil Serven: Right. You type C-A-T-asterisk, and then you get words like catamaran and cat's paw and catastrophe. And it also turns up in sports. It's the term that they've chosen for setting up playoff systems, where teams that automatically qualify by meeting the goal of being first place in their divisions, they are automatic. But then there are other teams that need to fill out the playoff bracket. And so they aren't necessarily automatic winners, but because they reached a certain record, they get selected as wild card teams. The NFL uses a wild card system and so does Major League Baseball. So that's another way we've used it. There's nothing really unpredictable about it, but it's probably goes back to drawing, like the way cards are selected for who gets to qualify and who does not, somebody gets to be a wild card and then gets advanced to the tournament.

Emily Brewster: So there's uncertainty inherent in a wild card.

Neil Serven: Right. And so wild card, the term, dates to the early 20th century and was often used in phrases that extended the card game metaphor. So it would be used with verbs like to deal, to be dealt a wild card, to discard a wild card, to play a wild card. And later we've used the same manner of phrasing when we say to play other types of cards in rhetoric, of course, you can play something like a race card. You can play the woman card. You can use some kind of tactic that is deemed to give you some kind of advantage. And it's usually reductive. You don't say I'm going to play the race card now, it's someone else is accusing you of it. Usually when you bring it up as a subject.

Emily Brewster: Neil, are you saying that wild card dates to the early 20th century for the extended use or for the card game use?

Neil Serven: The card dates to the early 20th century. And then I've got a figurative use from 1947.

Emily Brewster: Those are both much newer than I thought. I think of wild cards and card games as being played since longer before modern entertainment.

Neil Serven: Right? And you would think because it's what we did to entertain ourselves, play cards and gather in parlors and whatever, before radio and television came along...

Emily Brewster: I looked into the race card some time ago. And I think I found that dating to the mid-1970s and first in British English, the British newspaper The Observer stated that "The Tory leadership declined to play the race card." So they declined to use the issue of race to their political advantage.

Neil Serven: Right.

Emily Brewster: You brought up woman card and Alexandra Petri, I believe is how she pronounces her name, a Washington Post columnist, who writes these really great satirical articles. She was writing one on the term "the woman card." And of course the woman card, as you mentioned, is the idea that you would use, the fact of one's being a woman to your advantage politically or socially. But her article took it and imagined the woman card as the kind of rewards card. Like your gas card that gets you extra points on whatever, but the woman card will get you a discounted wage. It'll get you...

Ammon Shea: 77 cents on the dollar.

Emily Brewster: That's right. 77 cents on the dollar. It'll get you more expensive hygiene products because they are pink, et cetera. It's a very funny column.

Neil Serven: There's also a phrase we should mention is play the trump card, which does not have anything to do with the 45th president, but it figuratively means a decisive overriding factor or final resource, but it does refer to its use in card games where it was a card of any suit that ranked higher than cards of any of the other suits. So that would be used in games like euchre and spades. Zadie Smith, in the novel White Teeth, she also uses this in a card game phrase. She says "For after all, she was the mother here, the mother of the boys in question. She held the trump card should she be forced to play it."

Emily Brewster: Now, a wild card can be used as a trump card. That's the great thing about a wild card is that a wild card can be any card.

Neil Serven: The wild card is ostensibly a card that it gives you such an advantage that it has power or value over other cards. What this leads me to is examples of so many other idioms and phrases in English that originate from card games.

Ammon Shea: Do any of these come from euchre? Because I would be so excited to hear some euchre-inflected English.

Neil Serven: Well, interestingly euchre itself can be a verb meaning to deceive someone, right? Just like snooker refers to the pool game. Same idea. Euchre can mean to do something deceptive.

Ammon Shea: You mean it can mean it in the sense of any word that you use to mean something can mean something or do you mean as in the sense of people commonly use it in this sense now?

Neil Serven: People do use it. Yes. I, as an editor at Merriam-Webster Dictionary, give you permission, Ammon Shea, to use euchre in this way.

Ammon Shea: I'm citing you as evidence. I'm going to do it.

Neil Serven: Okay.

Ammon Shea: As soon as I leave here.

Neil Serven: So an example is in the programs of Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression, trying to relieve the country from the Great Depression, he called his program the New Deal. Programs such as Social Security and the Works Progress Administration, and that referred to the idea that people were getting a new hand dealt to them at cards.

Emily Brewster: Oh wow.

Peter Sokolowski: Yeah. I had no idea. I took that deal to be sort of an agreement, not a literal deal of cards.

Neil Serven: Writers, such as Mark Twain had used the term previously with a similar metaphorical angle in Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court it said, "It would seem to me that what the 994 dupes needed was a new deal." And so I think journalists would then pick up the term and then kind of apply it to the idea of card games like, okay, we're cleaning up the table, we're going back to start and we're going to all be anteing up again, or having our pots refreshed. The idea was that people were just getting a new chance, they were struggling up to that point.

Emily Brewster: It's a great metaphor if your readership plays cards, right? Everybody gets a new hand. Everybody starts again at the same place.

Ammon Shea: Nobody gets euchred.

Neil Serven: Nobody gets euchred. And one from card games that I didn't know was from a card game is the term left in the lurch. So lurch is used in cribbage. Do any of you play cribbage?

Emily Brewster: I played cribbage with my grandparents when I was a kid. I don't remember how to play, but it was really fun.

Neil Serven: I think I played in college, but I couldn't tell you how to play now. Anyway, lurch refers to a decisive defeat in which an opponent wins end game by more than double the defeated players score. And so that comes from Middle French. The word lourche described a game similar to backgammon from which arose the use of the same term for such ignoble defeat. Another one that I would not have thought came from cards is aboveboard. I thought that was nautical when I first heard it.

Ammon Shea: I always assumed it was nautical.

Neil Serven: No, aboveboard refers to keeping your hands over the table. The board is the table when you were dealing. So if you keep your hands above board, people know you're not cheating and reaching for...

Emily Brewster: You're not sticking an ace up your sleeve.

Neil Serven: You're not sticking an ace up your sleeve, which is another phrase from card games.

Peter Sokolowski: Sure.

Neil Serven: Another one is follow suit. That refers to games like whist. I think it might actually occur in euchre too. You have trick-taking games where the object is to follow suit by playing a card that has the same suit that's been played before.

Emily Brewster: It's also similar to UNO. It's not suits, but it's a similar idea.

Neil Serven: UNO is basically based on those games where you're supposed to match either the color or the number that's been played before. Ace in the hole, which is sort of like ace up one's sleeve. Ace in the hole refers to the hole card, which is a card that's dealt face down like in blackjack. To have in spades is something to have talent in spades. It doesn't mean the amount that's going to fill a shovel that comes from card games. And then one of my favorites is according to Hoyle. Edmund Hoyle was the guy who wrote all the rules of card games. He lived in 1672 to 1769 and he wrote books including A Short Treatise on the Game of Whist. He wrote that in 1742. And his books were regarded as so authoritative, getting all the nuances of all these rules of all these different games and all these different variations of games, the phrase according to Hoyle entered our language, meaning "in full compliance with accepted customs."

Peter Sokolowski: According to the rules.

Neil Serven: According to the rules. Say the order of a parade, if you're trying to get all the people in their proper order for a parade, then once you did that, you would say everything was according to Hoyle.

Emily Brewster: I've never heard that in common use. I think that it's gone the way of card games. Did you ever go through a time period when you played cards?

Ammon Shea: Yeah I spent an entire summer playing canasta with a bunch of women who were a little bit older than me when I was 12. A group of elderly women who were where we had a summer place and they needed a fourth for canasta and they somehow roped me in it. I spent three months playing canasta.

Emily Brewster: That's great.

Ammon Shea: I loved it.

Neil Serven: There's a short story there. I played a lot of cards in college. It was something to do. And it was a way to earn money off kids who were more inebriated than you were.

Emily Brewster: Ooh.

Neil Serven: Yeah. Which I did.

Ammon Shea: You euchred them.

Emily Brewster: Yeah, you did euchre them.

Neil Serven: Which I did. Yes. But we didn't play euchre though.

Ammon Shea: It doesn't matter. I got to use euchre as a verb since you brought it up, my day is complete.

Emily Brewster: Let us know what you think about Word Matters. Review us wherever you get your podcasts or email us at [email protected]. You can also visit us at nepm.org. And for the word of the day and all of your general dictionary needs visit merriam-webster.com. Our theme music is by Tobias Voigt. Artwork by Annie Jacobson. Word Matters is produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. For Neil Serven, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, I'm Emily Brewster. Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.