Most adjectives can be ranked — something can be good, better, or best — but are there any that can't? Are some adjectives already absolute? Does the English language love to confuse and beguile? We'll get into that, plus the tricky usage of than in phrases like "than I" and "than me."

Download the episode here.

Transcript

(intro music – “Build Something Beautiful” by Tobias Voigt)

(teaser clips)

EMILY BREWSTER, HOST: The dictionary recognizes than as both a conjunction and a preposition because it is. We know it is because it acts like one.

AMMON SHEA, HOST: We need to talk about whether something can be "more unique" or even, perish the thought, "uniquer."

(music interlude)

EMILY: Coming up on Word Matters, absolute and gradable adjectives, and what kind of a word is than? I'm Emily Brewster, and Word Matters is produced by Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media. On each episode, Merriam-Webster editors, Neil Serven, Ammon Shea, Peter Sokolowski, and I, explore some aspect of the English language from the dictionary's vantage point.

(music break)

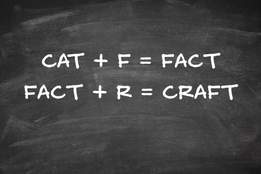

EMILY: Let's talk about adjectives. Typically, an adjective can be graded according to degrees. Cute, cuter, cutest. Good, better, best. But some adjectives eschew such treatment. Something unique, for example, is in a class all its own. It can't be more unique than something else. Or can it? Here's Ammon Shea on gradable and not-so-gradable adjectives.

AMMON: Today, we are going to talk about gradable adjectives.

EMILY: Woo-hoo!

NEIL SERVEN, HOST: Gradable?

AMMON: So I hope you all have your gradable pants on.

NEIL: Our grading pens?

AMMON: Yes. People like to hold or at least to try to hold the use of words, sometimes, to similar scientific principles that apply to say Newtonian physics. An object will remain at rest or in uniform motion or in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force. I think while there are certainly some aspects of our language that are a bit changeable and fuzzy—otherwise we'd all be speaking Old English—but there's this feeling that there must be certain bedrock principles that have to remain unchanging. And perhaps, foremost among these, is the belief that our language has some adjectives which must remain absolute.

PETER SOKOLOWSKI, HOST: Oh right, like unique?

AMMON: Right. Unique is a perfect example. But there are a lot of absolute adjectives, which in the words of Joseph Wright, who in 1838 wrote far too many words about this subject, an absolute adjective is something that will admit no variation of state.

EMILY: Can you give an example?

AMMON: Unique is a good example of an absolute adjective because people like to say that something is unique or not. One of the classic examples was "I was pregnant," because you're either pregnant or not. However, a lot of words in English have more than one meaning. So, even though if we're talking about a person being pregnant, it tends to be an absolute use of the adjective. People either are typically pregnant or not pregnant, but if we're talking about a series of increasingly pregnant pauses, you could say there was a series of pauses, each more pregnant than the one before it, because pregnant obviously does not just mean with child. It can mean a number of other things. And so when we're talking about adjectives, what we need to I guess look at, is that if we want to use slightly less flowery language than Joseph Wright and his "no variation of state," people tend to think of adjectives as being of one of two kinds, either gradable are non-gradable. So a gradable adjective would be good. Something could be good, it can be better, it can be best. Wide, wider, widest. And then we have the non-gradable ones or the absolute ones, such as pregnant and then dead. But also dead is kind of like pregnant, subject to extended meanings, like a piece of wood that resonates can be dead if it doesn't resonate. So you could say this viola is deader than the other one.

EMILY: Deader than a doornail.

AMMON: Exactly. So we see an idiomatic use as well. A ball can be dead. And if one ball can be deader than another, or if one violin can be deader than another, then obviously that means that there is nothing sacred in this world. All the rules are thrown out the window. The center cannot hold. Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, or at least upon the English language. It means that we need to talk about whether something can be "more unique" or even, perish the thought, "uniquer."

NEIL: Oh my goodness.

PETER: Or most unique.

AMMON: Right. This is when people listening start getting out their pens and dipping them in blood and writing angry letters. We define unique in the ways that you would expect, which is things like "being the only one," "being without a like," or equal and so on and so forth. But we also define it simply as "unusual." And we are neither unique nor unique in either sense you choose to use among dictionaries in offering this unusual definition. Every single dictionary or every modern dictionary does it.

PETER: Sure.

AMMON: Now, why do they all define it this way? Is it because we all hate the English language and there're people who cherish it? No, it's just because enough people use unique in a highly gradable fashion that it warrants the century. Louisa May Alcott, Walter Scott, Charles Darwin, and thousands and thousands of other writers over the years have used "quite unique," "more unique," "somewhat unique," and things like that. Do you guys have any adjectives that you personally feel are absolute?

EMILY: If we are talking about non-gradable adjectives, then perhaps we can think of numbers. Sequential. Can something be, say more or less 17th? No.

AMMON: Right.

EMILY: So there is a whole gigantic category of non gradable, absolute adjectives, which are number adjectives.

PETER: Most people don't think of that.

AMMON: Yeah. That's such a great example. What people usually default to when they want to make something sacrosanct as an adjective or things like perfect or supreme, both of these are obviously routinely modified. And one of the most famous examples is the preamble to the U S constitution, which begins with "We the people of United States, in order to form a more perfect union." That does seem like it is remarkably non-degradable.

NEIL: It's interesting because I think that phrasing more perfect union. It's like they've written it with the idea that, the ideal of perfection is not going to be ever attained. And so they're trying to get as close to it as possible. So "more perfect" is the idea, it's like perfect in that sense almost doesn't mean perfect. Perfect means almost as close to perfect as we can get.

AMMON: Right. Like Zeno's paradox of perfection.

NEIL: Exactly.

EMILY: Never getting to the other side of that stadium.

AMMON: I feel like we're at the tail end of people trying to make certain adjectives absolute because nowadays we hear about unique, we hear about perfect, occasionally supreme, things like that. But about 200 years ago, there were a lot more, it was much more common to say that there are these adjectives, which permit no variation of state and Joseph Wright, the fellow we mentioned earlier, who wrote about these adjectives in 1838, he very helpfully included a list of non-degradable adjectives in the book he wrote, which was called A Philosophical Grammar of the English Language. And what he felt among many others were not gradable were dead, right, straight, round, clear, entire complete, empty, perfect, chief, extreme, proper, just, immediate, supreme, dumb, flat, directed, unbounded, real, positive, visible, innocent, odd, secure, wet, free, false, exact, unlimited, immeasurable, dry, evident, obvious, certain, deaf, pure, excellent, equal, guilty, genuine, sterling, eternal, full, plain, superior, universal, even, level, honest, fair, true, untrue, chased, steady, perpendicular, apparent, absolute, blind, unjudged, correct, silver, punctual, harmless, determined, accurate, permanent, incomprehensible, everlasting, omnipotent, et cetera. He also said that all the colors were non-gradable.

PETER: So his problem is he's confusing logic with language, right? Because he thinks round, for example, it has to be perfectly round. And yet we know that that's not true in life. The phenomenon of things that are round often require alteration or something could be more round than something else, or less round.

AMMON: I think that may have been true for certain words like round or perpendicular-

PETER: And wet.

AMMON: But sober I think is a little more judgmental than logical. Peter Sokolowski: But this is a problem I think that we all have to address as language professionals, which is the sort of encounter between logic and grammar, encounter between logic and etymology, because they're two different things. And it's a distinction we try to draw when writing definitions, which is that we're defining the word. We're not defining the phenomenon. So like the definition of love, for example, is supposed to reflect the way this word in this spelling is used in text. It's not supposed to actually define your sensation of an emotion.

AMMON: I think of it more as a knife fight than an encounter personally.

NEIL: Well, I think for like Peter, your example of wet, you know, yes I can think of there being absolute categories of wet and dry. Right now, the counter is dry. I sprinkle a little water on it. Yeah. Now it is wet, but I could also take more water, pour it all over the counter, and then the counter is wetter. Wetter in the category of wet. It is a subset of the state of being wet. And so wet has great ability within itself in that regard, despite the fact that it is completely absolute from the concept of dry.

PETER: Yeah.

EMILY: I still feel like this guy, what was his last name?

AMMON: It was Joseph Wright.

EMILY: I feel like he lived in a different world than we live in. A world where absolutes existed in a way that they just don't anymore.

AMMON: Yeah. Well, it really started the idea of the absolute adjective began in the 18th century with the grammarians like Lowth and Murray who really may be a little more inclined to apply rules to the language than many of us are today.

EMILY: I feel like there's something laudable and I have sympathy for them wanting to make these categories, to make them actually be more stable than they are. But my sense, having done lexicography for a while now, is that there's just very little in the language that fits perfectly well into a category,

AMMON: But you've given them 17th. And for that, they will always have 17th.

EMILY: That's right. Actually it's infinite, there are infinite absolutes.

AMMON: You've bequeathed them an infinite number of absolute adjectives.

PETER: Yeah, that's right. It's interesting that you're talking about the period of the Age of Enlightenment, which really was a period during which there was a mania for people to catalog things. It's when Diderot came up with the encyclopedia, it's when Johnson wrote the first modern dictionary of English, it's when the Encyclopedia Britannica came up. Those three things happened within about 25 years of each other. So there was this incredible mania for categorization and putting things in little boxes. And that's exactly what this is. They said, well, let's identify language with a taxonomy, the way that we would in the sciences. And that was always the goal. And I'm sure a lot of them were very confident, as was Joseph Wright, about their taxonomy. But looking back, I don't think that necessarily there was a golden age of un-gradable adjectives. I just think there was a golden age of people who were describing them in those terms. And it's interesting for us to step back and say, okay, well, the Enlightenment was essential in order to categorize so much, but actually they were putting those boxes maybe in the wrong places or they were making them much too solid or much too specific.

NEIL: Ammon, I think you mentioned the word superior in your list. Didn't you?

AMMON: I think I did.

NEIL: That strikes me as very unusual because I think of that as being a gradable adjective in itself.

AMMON: It's inherently gradable.

NEIL: A gradable version of super, if you are a superior to something you are more super. I don't know if it's always had that meaning, but it strikes me that how naturally we turned to gradability in our language when we are modifying adjectives. It's always about something being in relationship to something else and that unique gradability when you are comparing two things, that's what it's exactly for.

PETER: And that's how adjectives work. I mean, very heavy, extremely tall, mostly sunny. We have that pattern in the language.

EMILY: And those were examples of adverbs modifying adjectives, which is one of the ways that we make gradable adjectives.

AMMON: All this talk is making me feel a little bit unique, so we should wrap it up.

NEIL: You're very special.

(music break)

EMILY: You are listening to Word Matters. I'm Emily Brewster. We'll be back after this break with an exploration of than. Word Matters is a production of Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.

PETER: I'm Peter Sokolowski. Join me every day for the word of the day. A brief look at the definition and history of one word available at merriam-webster.com or wherever you get your podcasts. And for more podcasts from New England Public Media, visit the NEPM Podcast Hub at nepm.org.

NEIL: I'm Neil Serven. Do you have a question about the origin history or meaning of a word, email us at [email protected].

EMILY: We now turn our attention to something of a controversial four letter word. That's right: the word than. Does that grammarian over there know more than me? Or do I have to say than I? The answer depends on just what kind of word you think than is. I'll take a look at this controversial word. I was raised in a family that prized strictly proper grammar and usage. So one of the things that I was drilled on was the right pronoun to use after the word than. I was taught to always say that, my sisters are older than I am, not older than me, specifically older than I, not older than me. Any of you taught this?

NEIL: I wasn't taught anything.

AMMON: No.

EMILY: It was a topic of discussion in my house, which is maybe how I came to be here. What I didn't know until much later is that what this rule is really about is what kind of a word than is. If we say "she is older than I," we are treating than like a conjunction, which it is. If we say "she is older than me," we are treating than like a preposition. Now the dictionary recognizes than as both a conjunction and a preposition, because it is. We know it is because it acts like one, right? In "she is older than I," it's acting like a conjunction. In "she is older than me," it's acting like a preposition, but people have prescribed the conjunctive use only. The conjunction dates back to the 12th century. And just as a refresher for people, a conjunction is a word that joins other words together. Often in this case, especially with than, it's often joining a main clause to a subordinate clause. A subordinate clause is a group of words, it's got a subject and a verb, but it can't be a standalone sentence. So-

AMMON: Conjunction junction.

EMILY: Conjunction junction. So, in "she is older than I," that subordinating clause that than is supposed to be joining "she is older," too is shrunk down to almost nothing. And the idea is that it's actually, it's really a longer clause that's hidden from sight. And it's more fully, "she is older than I am." "Than I am" is a subordinating clause because "than I am" can't stand alone as a sentence, but it has a subject and a verb. This is what than the conjunction is doing. We chop off the am, we chop off the verb, but it's still there somehow, magically, secretly hiding. And linguists recognize and the dictionary recognizes, we as lexicographers recognize that this happens with words all the time. There are parts of sentences that we don't say. So that is what is happening with the conjunctive than. Now, than is also, though, a preposition. When we say "she is older than me," we are treating than like a preposition. A preposition is a word that joins, usually has an object and almost always a small word. And it tells about time, location, or it introduces an object. All those things you can do to a tree: to a tree, over a tree, by a tree, under a tree. So in preposition than, it's followed by an object and me is the object singular pronoun. So it's the object of the verb. So it turns out that the word than has been used as a preposition since the 16th century.

AMMON: Johnny-come-lately.

EMILY: It is a Johnny-come-lately, but it's still so old, right? This is the, what, 21st century now. It's the beginning of the 21st century. It's like a solid 400 years old. It wasn't until those 18th-century grammarians who started instituting all these rules about how the language should be used, that people started insisting that than was only a conjunction and that saying "than me" was wrong.

AMMON: Is there any circumstance in which "than me" would be considered correct?

EMILY: No. Well, not for-

AMMON: Not for your parents.

EMILY: It was mostly my grandmother really, but she made a really big impression, and not for my sisters who towed her line is why all the examples were "older than me" because they were older than I was. So, see? "Older than I." It was really impressed upon me to only say "than I."

NEIL: You kept getting reminded of your place too.

EMILY: I did. I really did. Yeah. In theory, there should be nothing wrong with than being a preposition, right? In theory?

AMMON: Yeah. I don't think so. But I feel like you've imparted to me a vague sense of unease that I will carry about with me.

EMILY: Really?

AMMON: Yeah.

EMILY: Wow. Awesome. Here's an introduction to something that may mess with that a good bit. Because you know, Bishop Lowth. Robert Lowth, who was a Bishop of England,

AMMON: Robbie.

EMILY: What was that?

AMMON: Robbie.

EMILY: He wrote a very influential book on grammar published in 1762 and it made a very large impression on many, many people. Many of the ideas that he had about what English should be like became rules that were imparted to students for hundreds of years. And he believed that than should only be used as a conjunction, but he had this crazy exception. He thought that when you wanted to use who or whom after than, you should use whom and whom is in the objective case, which means it's acting like than as a preposition, not a conjunction.

AMMON: In the glorious early days of the worldwide web, my favorite site that I ever came across was bishoplowthisafool.com. And sadly, whoever had that site lost the URL and it's disappeared.

EMILY: Oh, that's terrible.

AMMON: Yeah. It's a real crime. I feel like that's a site that should be visited daily by many, many people.

EMILY: I'm sure that's true.

AMMON: Yeah, because he deserved it in many ways.

EMILY: Yes. There's also a brand new book out about him that I think is trying to do a re-interpretation of him.

AMMON: The reappraisal of Lowth.

EMILY: Yes. By a writer named Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. But apparently what Lowth cared about was, well, he had this defense about whom after than. And his defense was that who only has reference to its antecedent and not to an understood verb or preposition, which feels basically meaningless to me. But what was more likely the issue is that Milton had used whom after than. And if John Milton does it, then it's got to be good English.

AMMON: Truer words have occasionally been spoken, but...

EMILY: Well, in some ways it's a very modern interpretation and reminds me of how we as lexicographers approach language. If something is used by speakers of the language, by writers of the language, especially if someone is a careful, intentional user of the language and they use something in a book, that tells us that this competent user of the language has used this word in this way. Oh, that's interesting. That tells us something about what that word's function in the language is.

AMMON: I agree with you, absolutely. My problem with that is that it frequently seems to be the people deciding these rules use a data set of one, which is their favorite writer. And they refuse to say, but the 5,000 peasants who used it this way last week, they're all wrong, because they're not the great men of literature.

EMILY: Sure. That's right. And the fact is that the 5,000 peasants are also competent users of their language. Every bit as competent to user of their language as a published author.

AMMON: Sure.

NEIL: What is interesting is that the question of function for than, which getting back to the original subject is only really becomes a matter of issue once pronouns are entered into the equation, because that's the only time you would change the case. You would say, John is taller than Mark. You don't know what Mark's function is there. You could easily append another linking verb. John is taller than Mark is, or if you want to get into better verbs, John has more cats than Mark does. Then Mark is subjective. "John is taller than Mark" then gets into, you don't know if Mark is really serving as an object or a subject there,

EMILY: Right. And you don't have to care. English has long since shed most of its grammatical cases, these forms of words that change depending on their placement in the sentence's syntax. English has just thrown most of those away. And we just have them lingering on in our pronouns. Lucky for us, it makes English a simpler language in some ways, and it makes English more flexible. English is more easily able to adopt new words into it from other languages because of this. I wonder also, though, if it means that we wind up with these issues that maybe people don't have so much in other languages, because we have a word like than, which you really don't know, because the question of what pronoun to follow it is an unusual question.

AMMON: It wasn't for me for the first 49 years of my life, Emily. Thanks.

EMILY: No problem.

(music break)

EMILY: Let us know what you think about word matters. Review us on Apple podcasts or send us an email at [email protected]. You can also visit us at nepm.org and for the word of the day and all your general dictionary needs visit merriam-webster.com. Our theme music is by Tobias Voigt, artwork by Annie Jacobson. Word Matters is produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. For Neil Serven, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, I'm Emily Brewster. Word Matters is a production of Merriam-Webster in collaboration with New England Public Media.